CONTENTS

- SUMMARY

- (COOP)YOUTH

- STUDENT

- EDUCATION

- WORK

- ENTERPRISE

- ECONOMY

SUMMARY

There are several terms and concepts that bear defining in order to ensure understanding of the philosophy and praxis in this toolkit. The explanations range from clear-cut statistical definitions (e.g. “child”) to philosophical interpretations (e.g. what is “work?”). These interpretations are oriented within the lineage of intergenerational cooperative philosophy outlined in the literature review - with special focus on Father Arizmendiarrieta’s contributions which directly named and defined many concepts, as well as the coopyouth philosophy espoused via the collection of coopyouth statements. In essence, much of this “Definitions” section and the following “Isms” section are a presentation of the coopyouth perspective on cooperativism, supported by elder philosophers and leaders.

(COOP)YOUTH

Within the International Cooperative Alliance, the Global Youth Network identifies “youth" as all people up to 35 years old. This definition was, saliently, determined for and by youth cooperativists. No lower bound is identified, but there are some other measures that inform a lower bound indirectly. Of additional consideration in the above definition:

- Need to distinguish between children and youth: Organizing and advocating for children is necessarily different from doing so for older youth, given their respective needs and priorities. For example, children are more consistently and categorically denied their personal agency throughout the world than youth; which greatly shapes how to organize and support each identity group. That said, there is some overlap between “children” and “youth” needs and identities, but children and youth are typically able to self-identify which programs or groups best serve them.

- Internationally, children are defined as anyone up to age 18, per the Declaration on the Rights of the Child authored by United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). It is worth noting that the Convention still affirms prison as an appropriate form of punishment for children, and that children as young as 15 are allowed to fight in wars. Despite the protections outlined in this Convention, children are not allowed to vote or participate in political processes, nor are they allowed to serve on the juries that often decide their fates.

- Relationship to Other Definitions: The international Cooperative Movement is unique among other international movements insofar as it has a century-old membership organization. As a result, its peer organizations, in terms of scale and scope, are by and large Intergovernmental Organizations: the United Nations, International Labor Organization, the G8 and G20, International Workers of the World Union, and their affiliates. A few of those within that peer group of scale and scope that define “youth” within their work provide the following guiding definitions:

- United Nations & Agencies: youth are aged 15-24

- African Youth Charter: youth are aged 15-35

- UNICEF: childhood ends at age 18

- Legal Age of Adulthood: In many places worldwide, children cannot be legally recognized owners of an enterprise (i.e. members of an incoporated cooperative) until they achieve legal “adulthood” (often age 17 or 18). Not all cooperatives incorporate with a regulatory entity, but for those that do, these legal constraints limit who can participate in a cooperative. In the context of formal (i.e. legally incorporated cooperatives), the lower age bound for coopyouth aligns with legal adulthood, while those cooperatives who choose or are forced to remain part of the informal economy may engage youth younger than the legal age of adulthood.

Some aspects of the “youth" identity and life phase that are important to keep in mind:

- Shifts In Financial Status: During this period of life, most people shift how and from where they obtain the financial resources they need to survive. Sometimes this means an individual being financially independent for the first time, as they cease being financially supported by their family. Other times, it can mean shifting from a regime of individual financial responsibility to shared responsibility within a marriage. As family structures or living arrangements change, young individuals must take on an increasing amount of financial obligation, many for the first time in their lives (e.g. paying for housing).

- Historical Movement Building Role: Youth have built collective power and agitated against injustice all over the world throughout history. Most recently, youth organizing helped to bring about the Arab Spring, the Ferguson uprisings, the Quebec Student Revolution, Nigeria’s youth protests against police brutality, and the direct calls led by students and youth to end militarization in Indonesia. While not every youth considers themselves a revolutionary or even sees value in agitation work, this has been one of young peoples’ most notable contributions to world history and societal progress. The reasons that youth engage in movement building often have to do with having “less to lose” in terms of resources, more energy and fewer daily responsibilities, as well as bearing the brunt of many of the injustices perpetrated by the older ruling class. For some, this period of life also brings individuals into direct contact with oppressive and inequitable systems of power for the first time, after being somewhat shielded by a family system or geographic isolation. For elders, over time, a person can become acclimated to injustice, especially as individuals’ earning potential often increases the more work experience they accumulate over time.1 This often shifts individual incentives for movement building, as priorities change and people have “more to lose.” The cooperative movement should strive to understand the politicization of youth through this material lens, rather than through infantilizing understandings of youth radicalization as a “phase.”

- 1 Lazear, E. (1976). Age, Experience, and Wage Growth. The American Economic Review, 66(4), 548-558. Retrieved June 15, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1806695

STUDENT

An identity that often overlaps with youth in the Cooperative Movement is that of student. In many corners of the Cooperative Movement, "student" cooperators have been engaged to represent youth, at-large, given this overlap. However, the majority of youth in the world are not students, nor do the majority of people in the world receive formal education during their youth life phase. And, increasingly, the cooperative model is of interest to those without access to advanced educational opportunities that can then put them at a disadvantage in pursuing conventional employment. The evolution of the Coopyouth Movement internationally is somewhat a reflection of this shift -- that students are a subset of youth, and are not sufficient representatives for youth, at-large.

Institutional Relationship: Coopyouth who additionally identify as students are most often, though not exclusively, those pursuing post-secondary education (e.g. university). As a result, coopyouth students face issues navigating a relationship with an educational institution that feels very intimate and intense, as it relates to their efforts towards self-betterment and/or pursuing a livelihood. In contrast to the other institutions with which youth may be coming face to face for the first time (e.g. nation-state, banks), colleges and universities ostensibly serve a majority youth student population, which can engender a very different kind of relationship and interaction that is more empowered and rightly entitled.

Transitory: Besides a unique relationship with an institution, another key aspect of the student identity is its transitory nature (as with youth!). Those organizing in student communities are examples of people doing work for more than just themselves, as student tenures tend to turn over at a higher rate than (educational) institutions can enact changes in policy or behavior.

Of the key issues coopyouth face, the key issue discussions of “Relationships of Coercion,” “Relationships of Solidarity,” and “Membership Transition” are of extra importance for those who are also students.

EDUCATION, WORK, & ENTERPRISE

The concepts of education, work, and enterprise have been distorted within mainstream society, to the extent their most common usages are now a reflection of capitalist ideals. “Education” is typically interpreted in an institutional sense, with regard to pursuing credentials from a formal educational institution. Those credentials, then, have currency when pursuing “employment” - or working for someone else, which has become falsely interchangeable with “work.” “Enterprise,” similarly, has come to be understood as “business,” though the term has a much broader application. The following section regrounds the concepts both in their grander historical interpretations, as well as those of cooperative philosophers and practitioners.

Education

Learning happens in all arenas of life; it is not a process relegated to formal educational institutions like universities and colleges. Father Arizmendiarietta, founder of the largest worker cooperative federation in the world, effectively initiated the federation’s first cooperative via an educational group that has now evolved into a university that still exists today. While his work has evolved into a formal educational institution over the past century, it began from a simple study group. He believed, “teaching and education are the primary undertakings of a community” and “the key to the fate and future of our young people and of our society” (1999, 48-49).

Within most conventional discussions of education, the value of education is measured by how “employable” it makes a person. Part of this corruption of education by capitalist values is the rise of “credentialism” within the job market. Many higher paying jobs have a baseline eligibility requirement for an applicant to have achieved a certain level of education and have a credential to demonstrate that achievement. In many places throughout the world, these kinds of credential education programs cost a considerable amount of money (e.g. university/tertiary degree). Rather than positioning education as a path of personal development and a way to enrich one’s life, it restricts it to a narrow role of elevating one’s economic status - if one can afford the correct credential and find a relevant job.

- Banking & Popular Education: Not only has education, as a concept, been distorted away from its more expansive role within society, so, too, have methods of “teaching.” In both the 2014 and 2015 CoopYouth statements, more participatory information sharing methods were called for, which was a critique of the Cooperative Movement’s predominant use of conventional “banking” forms of education at its events. Banking education perceives the learner as a bank in which information is to be deposited and maintained. It does not engage the learner as an equitable partner in the process, and it suggests that what is being shared is static knowledge - not to be changed or challenged. The term “banking education” was coined by Paulo Freire in Pedagogía del oprimido, in which he also outlined the concepts of “Popular Education,” which is “...a philosophical and pedagogical approach, which understands education as a participatory and transformative process, in which learning and conceptualization are based on the practical experience of the people and groups participating in training processes.”1

Cooperativism, similar to Popular Education philosophy, perceives education as a constant striving undertaken throughout one’s life, as an integral part of the human experience, and for which no credential can be purchased or awarded.

Work

First and foremost, in the context of this toolkit and cooperativism, as a discourse, “work” is not synonymous with “employment.” Employment refers to a relationship a person can enter into with another person (“employer”) or themselves (“self-employment”), in order to acquire money in exchange for their labor. Work is, instead, a much grander and universal concept. Father Arizmendiarrieta, in Pensamientos, put forth several powerful descriptions that speak to the full expression of this conception of work:

- “Work is the characteristic expression of the human species;”

- “Work is interpreted as intelligent action on nature, transforming it into a good, into something useful;”

- “Work is, above all, a service to the community and a way of developing the person;”

- “Work is a path of personal and communal self-realization, individual perfection, and collective improvement; it is the epitome of an unquestionable social and humanist consciousness; and”

- “The problem of our day is not how to find a way to escape work, but instead how to make work a service, and, where possible, a source of honest satisfaction. Work can and should be humanized” (1999, 62, 65, 67).

While the economic character of cooperative work is incredibly essential, its highest purpose is self-realization and collective liberation; matters of thriving, rather than just surviving within a harmful economic system by being employed in service to that system and its minority beneficiaries.

Enterprise

Arizmendiarrieta continues to flesh out the cooperative conception of work and begins to touch on the ever important “enterprise;” the organizational description chosen for inclusion in the Cooperative Identity.

- “Work is not a punishment from God, but proof of God's trust in people, making them his collaborators. [...] In other words, God makes people members of his enterprise, of the marvelous enterprise that is creation” (1999, 62-63).

- “Work is the attribute that awards us the highest honor of being a cooperator with God in the transformation and cultivation of nature and in the consequent advancement of human welfare. The fact that people exercise their faculty of working in union with their peers and in a structure of noble cooperation and solidarity gives them not only nobility, but also the optimal productivity to make every corner of the earth a pleasant and promising mansion for all. That is what work communities are for, and they are destined to help our people advance” (1999, 65).

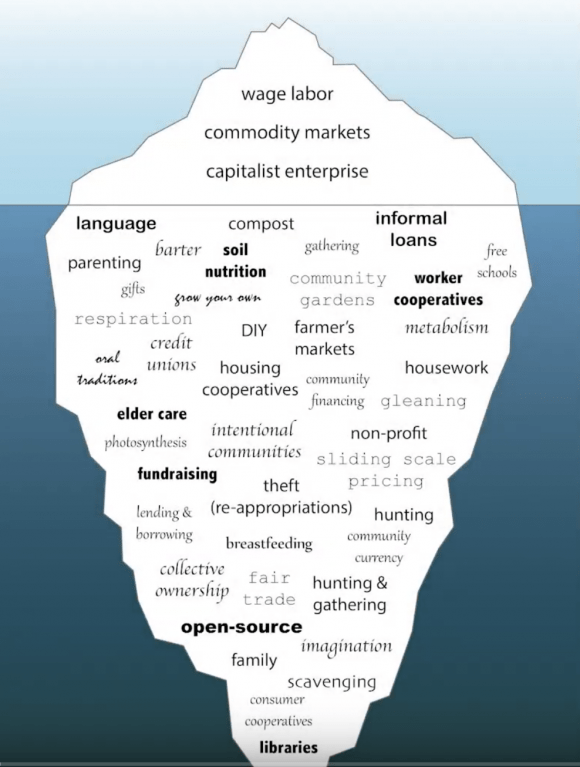

Enterprise, with this cooperative framing, is not synonymous with “business.” Rather, enterprises are “work communities” or social units in which education and training are the primary aims and mechanisms of collective effort. Cooperative understanding of education, work, and enterprise build on one another to create a social system that continually generates self- and group- actualization. Applying this framework to concepts such as “economy,” “movement,” and “community” can be incredibly transformative to one’s worldview, breaking it free from “capitalist realism,” or a widespread sense that capitalism has and always will be the only way in which to structure society.2

- 1 https://sites.google.com/site/conceptosdeeducacionpopular/concepto-de-e…

- 2 For a deeper discussion of “capitalist realism,” refer to the “Capitalism” sub-section of “Isms.”

ECONOMY

An “economic system” or “economy” broadly encompasses production, distribution, or consumption in a given geographic area. In an increasingly digital world, more economies are coming into existence that are not geographically distinguishable (e.g. clout economy, in which social influence is redefined as digital commodity, theoretically available to excahnge in a marketplace of arbitrary values). Production, distribution, and consumption of goods (including currency) and services may happen in a single household that can be delineated as part of several different economies, some trading in fiscal capital and some not:

- Sue agrees to follow her sister’s crush on Twitter if she posts an announcement for her upcoming event in exchange (clout)

- Stephen sells his old bike, which he received as a gift, to a friend from school for $200 (informal)

- Saiorse orders a hair clip she saw at the store for $5 on Amazon.com for $3 (formal)

- The neighbor brings over an apple pie after their tree has a bumper crop (gift)

Essentially, economic systems have relatively arbitrary bounds of definition that are selected according to what kinds of exchange the person defining the system wants to explore. Exchange of goods, services, and various forms of capital happens in an incalculable number of ways at an even more so incalculable rate. Study of economy is simply an endeavor to try to comprehend and conceptualize all of these infinite exchanges across time and space; however futile it may seem.

Some of the various overlapping and intertwining categories used in economic classification are as follows, with this list focusing on more general categorizations rather than specific, niche system concepts:

- Informal – investment, production, and distribution beyond the scope of government oversight or regulation

- Formal – investment, production, and distribution tracked and regulated by government

- Gift – giving away goods, services, or wealth without obligating a return of any kind (though typically return occurs “voluntarily” according to unenforced social norms)

- Barter – exchanges of goods or services without the intervention of currency

- Planned or Command – investment, production, and distribution is dictated by a central government

- Unplanned or Market – investment, production, and distribution is dictated by “supply and demand” (e.g. if there is a large supply and little demand, prices are low)

- Mixed Economy – A blending of various economic systems, which is generally present in all geographies throughout the world

The cooperative enterprise, based on Principles and Values, does not belong to any specific economy. Cooperatives have existed “under all kinds of governments, within every kind of economy, and amid all the divisions [...] that typify the human condition” (MacPherson, 1998, 219). Cooperatives exist in the formal (regulated by government) and informal (unregulated) economies. “The boundaries between formal and informal are not as important to organizations that are used to dealing in the market economy as a whole.”1 In fact, as is discussed in the “Dirty Words” discussion later in this section, a common misunderstanding many people have is that “marketplace” is synonymous with “capitalism,” when the truth is that there are many kinds of economic exchanges that can take place in any given marketplace and marketplaces may overlap, as illustrated in the household example above.

- 1 Birchall, J. “Organizing Workers in the Informal Sector.” (2001), p.viii